A very brief history of the invasion of Normandy. The Allied armies made it ashore on five beaches on June 6, and in the next couple of weeks advanced inland a few miles before basically getting stuck in the countryside, blocked by strong German resistance and by the narrow lanes, hills and hedgerows (embankments dividing fields) of the area. The Allies spent about six weeks grinding through these obstacles, and then suddenly broke through the weakening German defenses at the end of the July. The Germans were doomed by the fact that all potential reserves had been sent to the Eastern Front and by Hitler’s orders requiring impossible counterattacks or barring retreat. When the Allies did break through they liberated most of France, including Paris on August 24. The fourth map in this article dramatically illustrates these events.

https://www.vox.com/2014/6/6/5786508/d-day-in-five-maps

One more thing about the tides – in Normandy the difference between high and low tide can be 200 or 300 yards more of beach. Here’s a picture of one of the British beaches at very low tide. Fortunately the Germans barely defended the beach so the extra distance didn’t matter.

We visited several sites important to the British part of the invasion. At Longres Sur Mer the Germans had four large pieces of artillery that could fire right onto the landing beaches. The Allies heavily bombarded them by plane ship before and on D-Day. The Allied ships hit a couple of the guns, stunned the crews of the other two, and cut the telephone lines running from the observation post overlooking the beaches.

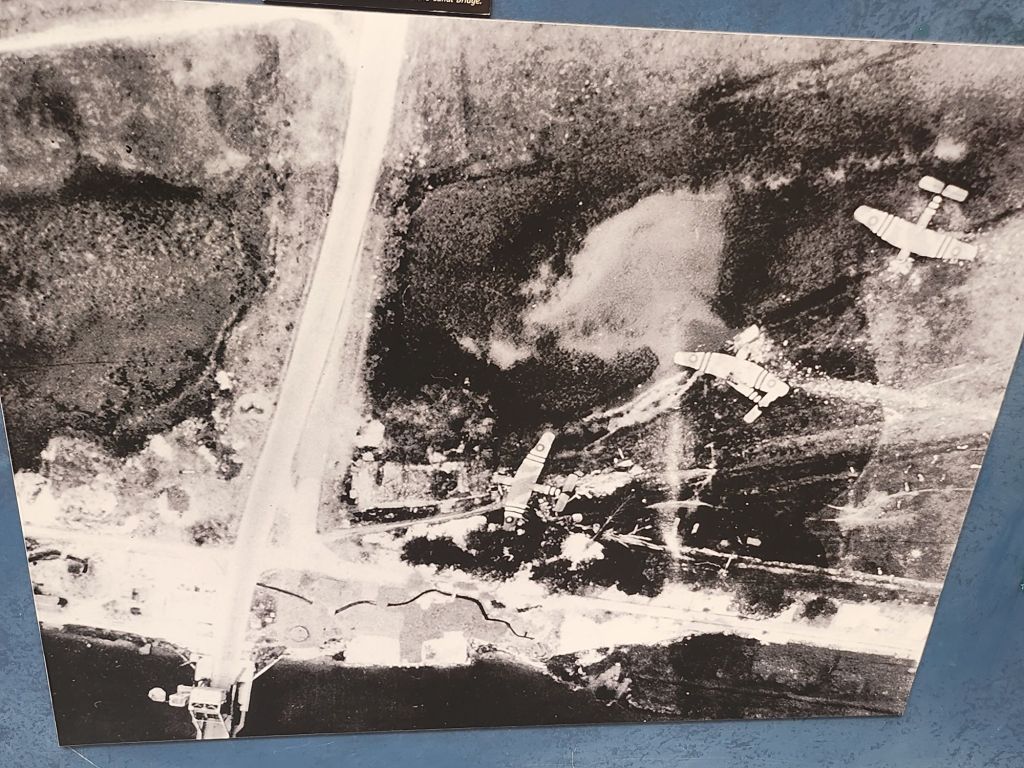

We went to Pegasus Bridge, the site of a successful D-day glider operation. The bridge was the best way over a canal just a few miles from the British landing at Sword Beach. By taking it the Brits could stop German reinforcements from coming to the beach and preserve it for the Brits’ own advance. The Brits planned a glider attack, in which gliders full of troops were towed by cargo planes and released at several thousand feet to glide to their targets. Even though the general commanding the operation was named Pine-Coffin, they executed it perfectly, landing three gliders just a few hundred feet from the bridge, taking it from the very surprised German guards, and holding it for a day until the troops from the beach came up.

A wartime photograph showing where the gliders landed; the bridge is at the lower left.

The bridge.

We visited the site of a British paratrooper attack aganst a German artillery position at Mierville that could fire down on the landing beach. This attack was also successful, but with greater loss of life.

Every museum or site we visit has a gift shop, and every gift shop sells D-Day Monopoly, which seems kind of inappropriate. I looked at a copy to see that Boardwalk was Omaha Beach and Park Place was Pointe Du Hoc, a cliff successfully attacked by American paratroopers. But I also saw that the two cheapest properties (Baltic and Mediterranean in the regular game) were Pegasus Bridge and Mierville. Our British guide vowed to write an outraged letter to Parker Brothers.

Bomb crater at Pointe Du Hoc.

There were hundreds of these craters in the square mile around the cliff. There were once tens of thousands such craters near the beaches, but they have been filled in the towns, roads and farm fields.

We visited several British cemeteries. They were more individualized and intimate than the American one, with flowers and messages on the gravestone from the families. Our guide said the goal was to recreate the feeling of an English country churchyard. The most moving was the smallest.

Too much death and violence. As we walked around yesterday, I saw a farm field that helped me understand why Impressionism developed in France. Then I saw several more fields, and one seascape.